Boeing Corporation released a video recently announcing the development of a new metallic material, considered to be the lightest ever created. And depending on who you ask, it probably is. But over the last several years there’s been a lot of talk about which is the lightest – we keep pushing the boundaries of material science, chemistry and physics, with some very interesting results. Let’s take a look at what’s out there now, what’s coming, and what it means for the world of manufacturing and prototyping.

Ultralight materials are considered to have a density of 10mg per cm3 or less. To put that into perspective, ambient air has a density of 1.2mg/cm3, so ultralight materials are just over 8 times heavier than air or less. Among this elite group we have the following lightweight contenders for the crown:

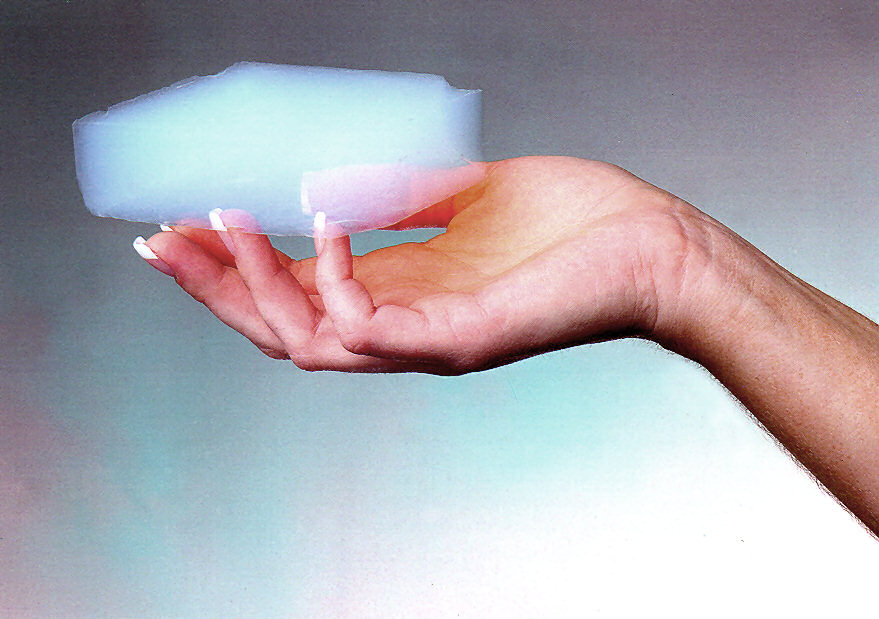

Aerogel

Not so much a single material but actually a class of materials which share a similar crystalline structure and which are made using roughly the same chemical process. Aerogels are sometimes called frozen smoke because of their characteristic foggy, light-scattering appearance. Aside from being light, they also have some wonderful mechanical properties. Because they are 99.98% empty air they make great thermal insulators – in fact, the best in the world, and that’s currently their main use.

Aerogels are so named because they were originally derived from liquid gels, in response to a friendly challenge between two competing chemists way back in 1933. The liquid in the gel was evaporated under controlled conditions, leaving behind only the solid particles which had previously been in suspension and which now fused together into a solid skin. New alloys coming out on the market are more flexible and plastic-like, so they can be machined and made into durable consumer goods. (Like the body of Google’s Nexus tablet).

Aerographene

Recently developed at Zhejiang University in China, this is currently the reigning champion, the lightest solid material known (as opposed to a gas or plasma). Just how light, you say? How about .16 mg/cm3, making it much lighter than ambient air and lighter even than helium. So why doesn’t it float, you ask? Simply because there’s air contained inside its internal chambers which makes the whole somewhat heavier.

Important to us here, and similar to aerogel above, is that this is a foam. (Hence, sometimes this entire class of materials is called nano foam.) That is, it’s a random, amorphous structure filled with holes. A lot of holes. There is so much exposed internal surface area that one single gram of the stuff, if you spread it out flat as could be, would cover an area of hundreds of square meters. And, because of this extreme porosity, aerographene can absorb 900 times its own weight in liquids, which may make it a great oil-spill sponge in the future.

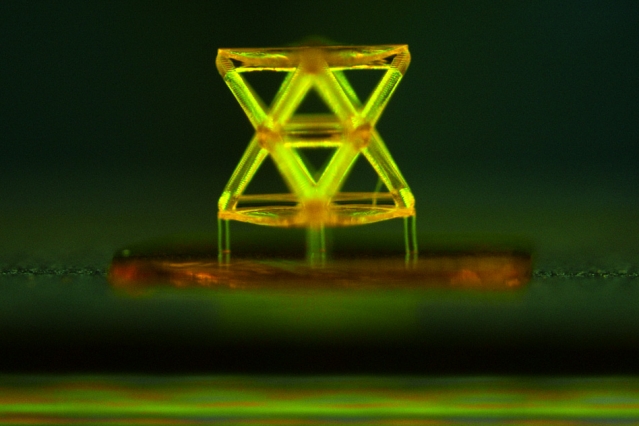

Metal Microlattice – The Lightest Metal on Earth

Going back to the picture at the top, the good people at Boeing’s research division HRL Laboratories made this in conjunction with GM and DARPA. “Lattice” in this case refers to the internal support structure which gives the material incredible strength to weight. The lattice construction also differentiates this material from the others, in that it has a regular, hierarchical and uniform geometry that is specifically engineered rather than being random such as with a foam.

And, it was made with 3D printing! First, a template is formed which creates the essential architecture, using a photosetting polymer just like with SLA. UV light cures the photopolymer which creates a three-dimensional form of struts and supports. Then, that template is plated with electroless nickel, like the coating techniques we talked about before. The plating is thin, only a few thousandths of a millimeter. Finally, the template material – the supporting thermopolymer – is removed using an etching process, leaving behind only the thin metallic skin and nothing more.

Voila! The lightest metal ever created. Well, sort of. It’s not a new molecular material per se, but it’s a new way to arrange the particles of a known metal on the micro scale. This is one of the great potential advantages of 3D printing– to create complex geometries on the nano scale that are precisely engineered to take advantage of a material’s best properties while literally trimming off all the fat.

Expect to see more of this in the future, and expect this type of technology to trickle down from academia and research labs to the more prosaic manufacturing hubs. After all, weight is always bad, right? Well, not always. There are cases where manufacturers intentionally add weight to a consumer product to give it heft and substantiality, which suggests high quality. (Think Beats headphones.)

But when performance matters most, selective and discreet applied engineering at the nano scale is going to be the best way to make the strongest, lightest anything, and 3D printing – in one of its many derivations – is going to make this possible.